Why might anyone care?

If you asked anyone familiar with Florida’s estuaries, “what do redfish eat?”, I imagine the answers wouldn’t be surprising. Little fish. Crabs. Shrimp. Pinfish. How right would they be? That could matter for a few reasons. First, some people, scientists or not, are just plain curious about the nature of aquatic foodwebs and want to know how the work. Fair enough. Second, maybe redfish diet information helps anglers trying to catch redfish—match the hatch, so to speak. And third, increasingly there’s a branch of fisheries science trying to assess the status of “forage fish” populations that support larger fish species—which, you know, requires knowing what fish are actually “forage”. All together, I thought “what redfish eat” was at least moderately interesting.

What I wanted to find out

So, to answer what redfish eat, I first made the question a bit more specific, because science. Seriously though, you really have to. The question “what redfish eat?” could be correctly answered with just about anything that a redfish has eaten, sometime, somewhere. Have I eaten sea urchin? Yes, but that isn’t descriptive of what I normally buy at the grocery store. What I really wanted to know was “what are some of the most important diet items to redfish?”. Unfortunately, answering that question has two complications:

- How do we define importance of a prey item?

- What size redfish are we talking about?

The first issue—how to define importance—doesn’t have a great answer. What’s the most important part of your diet? Is it the food with the most calories? The food you eat when you’re hungriest? For fish diets, there are a couple established metrics we use as possible proxies for importance. The one I’m going to use here is % volume—i.e. how much of the total volume of diet is a certain species. Just know there’s other ones out there I could have used.

The second issue requires more explanation. Different diet items might be important to fish of different sizes, or stages. One of the most important fish life stages is the recruitment1 stage. During recruitment, fish survival depends on fish density—i.e. survival is density dependent. Greater density (numbers of recruiting fish per area) should have lower survival, and lesser density should have greater survival. But how much density affects survival may depend on things like habitat (e.g., salt marsh grass), or availability of food. My point is that while all sizes of redfish need food, food availability can especially affect redfish populations during recruitment. So, what I really wanted to look at:

- What recruiting redfish eat (by volume)

- What all redfish (i.e. mostly larger) eat (by volume)

What I actually did

I answered these questions using data collected by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) Fisheries and Wildlife Research Institute (FWRI), which has a specific program for collecting scientifically-sampled data about fish, called the Fisheries Independent Monitoring (FIM) program (Flaherty et al. 2014). Basically, there exist scientifically collected data about diets of different predators, including redfish (Hall-Scharf et al. 2016). I just queried, sorted, and calculated these data to answer my questions. Here’s what I found:

The table shows the top ten diet items by volume. What that means is out of all the volume of diet items in all the redfish sampled (148 recruiting redfish, 1,373 total redfish), these were the top 10 items by percent of that volume. Recruiting redfish are on the left (light blue highlight), and on the right (highlighted in light green) are what all redfish, regardless of size ate. For each size of redfish, I listed the scientific name of the diet item, then the common name/group, because, and I’ll be honest, I was Googling most of these myself. One of the ones I didn’t have to Google? That would be the top item for the all-sized redfish (right, green): Lagodon rhomboides—i.e. pinfish. Yep, redfish eat pinfish, what a surprise. And after that, it’s pigfish, another fairly common prey species. While I was a bit surprised that these two species accounted for >50% of the volume (that’s a lot!), their identities were rather expected. But that expected result shouldn’t keep you from the other, maybe less obvious one.

Recruiting redfish eat very differently than the all-size group. Scan down the middle (name/group) of each side—recruiting redfish are eating mostly crustaceans, and most of these are small (mysids and amphipods are often 1cm or less long), whereas their bigger brethren are eating mostly fish species, plus some larger crabs. I should point out here that the all-size group includes much larger fish (like say 15” and up), as well as the recruits. I could have completely separated them—recruiting fish and then just larger fish, but I didn’t because I wanted to make this point. If you just looked at “what redfish eat, by volume”, you’d get what’s on the right, in green. That would be an idea about what counts as “important” redfish forage that is really quite different from what items likely are important to redfish during the most critical part of their life stage—recruitment. Another way to say this is that the some of the most important diet items for one of Florida’s most important sportfish are small, often unnoticed and really not-that-well monitored (from a scientific perspective) crustaceans.

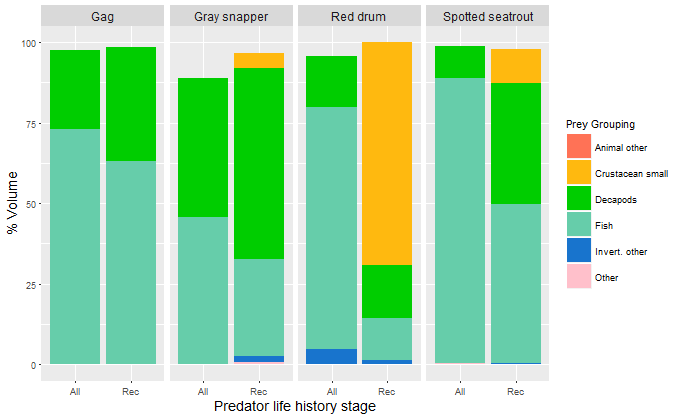

Wait you say, isn’t that expected—that little fish will eat differently that large ones? Yes and no. Sure, the diet item size should be different depending on the predator size, but the redfish shift in diet items themselves seems like a pretty substantial one. To see how it compared to other species, I repeated the methods here for gag, mangrove/gray snapper, and spotted seatrout, and compared how major prey groups differed between recruiting fish and all fish. Here’s what I found:

This is a stacked barplot figure for four common Florida sportfish—shown in the gray blocks with headings at the top. For each species (e.g., gag, red drum), the column on the left is diets of recruiting fish, and the one on the right is diets of all-sized fish. The color blocks in each column represent the major prey groups (see the PreyGroup key on the right). You see that while there are some differences between what recruiting and all-sized fish ate, by far the biggest visual difference is for redfish (err, red drum). So what this means to me is that the size-based differences we see in the table for redfish diets are pretty pronounced. Recruiting redfish diets really feed quite differently than the overall population does.

There’s a couple other things I should mention about that table, and the study in general. Where are shrimp at? Farfantepenaeus spp. are the penaeid shrimp—like brown, white, or pink that most folks will be familiar with as bait (or food), and they show up as important for the recruiting fish. Also, the third item for all-sized redfish, Actinopterygii (unknown fish) just means the folks analyzing the diet couldn’t tell the species of fish that got eaten. I’ve looked at a lot of diets, and it’s basically detective work. Sometimes, the items are just too digested to sort out what it was.

Finally, a couple caveats (things to keep in mind) about this study. Most of the redfish diets shown here came from the Tampa Bay region—and all were from the Gulf coast of Florida. The results might look quite a bit different if there were most samples around say, Cedar Key, or Apalachicola, to say nothing of the East coast. Second, remember that this little look just used % volume. That table would look different if I used use other metrics to represent importance, like number, frequency, or caloric content.

So, yeah. If that random person you asked about what redfish eat told you “I dunno, probably pinfish and shrimp”, well, they would be more right than wrong. But there is a bit more to the story—the little redfish are eating (little) shrimp and other crustaceans, and the larger redfish are eating pinfish (and other fish). As some scientists are increasingly recognizing how availability of forage fish can affect recruitment of juvenile fish (van Poorten et al. 2018), these results make me more interested in understanding how the small crustacean community that’s probably important for recruiting redfish is or isn’t changing with changes in freshwater flow into estuaries, habitat, etc. And also it maybe gives me a bit more confident using a gold spoon, or other pinfishy-looking lures.

References

Flaherty, K.E., Switzer, T.S., Winner, B.L., and Keenan, S.F. 2014. Regional correspondence in habitat occupancy by Gray Snapper (Lutjanus gresius) in estuaries of the Southeastern United States. Estuaries and Coasts, 37:206-228.

Hall-Scharf, B.J., Switzer, T.S., and Stallings, C.D. 2016. Ontogenetic and long-term diet shifts of a generalist juvenile predatory fish in an urban estuary undergoing dramatic changes in habitat availability, Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 145:3, 502-520

Van Poorten, B., Korman, J., & Walters, C. (2018). Revisiting Beverton–Holt recruitment in the presence of variation in food availability. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 28(3), 607-624.

Notes

1During recruitment, fish survival depends on fish density (survival is density dependent), then after recruitment, it’s usually density Independent. This means the recruitment processes set the “year class” of fish that enter the fishery (i.e. a “good year” for redfish means there was greater than normal recruitment about one year previous).